The PPIE at 100

December 10, 2015 § 2 Comments

By JEROME TARSHIS

The New Fillmore

Like California itself, like the fair of which it was a part, the art exhibited at the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915 looked two ways.

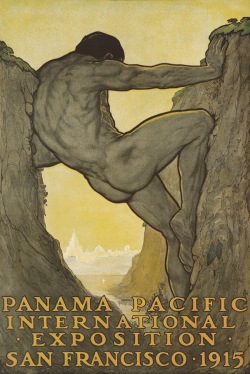

In principle the fair celebrated recent accomplishments made possible by big money and entrepreneurship: the completion of the Panama Canal and the rapid rebuilding of the city after the earthquake and fire of 1906. From the time of the Gold Rush, San Francisco had been a place where people could make a lot of money very quickly by exploiting the latest technology. Taking the edge off that reality, the city cultivated an image of Mediterranean charm, offering food, wine and art — in addition to venture capital.

The artistic aspects of the fair also looked two ways. Its buildings were in soothing pastel colors; the architecture looked back to a tranquil agrarian past; but many of the exhibits were devoted to the high-speed wonders made possible by machines and electricity and gasoline if not yet by silicon.

The De Young Museum’s “Jewel City” show reflects both aspects of the fair. From all accounts, the more than 11,000 artworks exhibited at the fair must have included vast swaths of instantly forgettable art, and the 200-odd works exhibited at the De Young certainly offer many soporific moments.

The De Young Museum’s “Jewel City” show reflects both aspects of the fair. From all accounts, the more than 11,000 artworks exhibited at the fair must have included vast swaths of instantly forgettable art, and the 200-odd works exhibited at the De Young certainly offer many soporific moments.

Among all the academic genteelism and quickly pleasing Impressionism, however, there are more than a few pleasant surprises. Here a portrait by Oskar Kokoschka, there a provocation by Edvard Munch, and even among the usual suspects as they would have been listed in 1915, strong work by Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent, among others.

The gallery devoted to pictorialist photography looks tranquil enough. By way of a surprise, the exhibition offers the earliest known work of Ansel Adams, a soft-focus print made when he was 13 years old. His father, far from keeping the boy’s nose to the grindstone, gave him a PPIE pass and ordered him to go to the fair every day instead of wasting his time in high school.

“Prints of the Fair,” a supplementary exhibition on the main floor of the De Young, is worth more than a passing glance. Predictably, it offers high-quality work by Whistler and other artists who were influenced by Japanese art and design. Less predictably, it offers a far less tranquil section of prints addressing the urbanization and mechanization of America.

The exhibition ends with a gallery of avant-garde art that pushes a bit farther than New York’s Armory Show did in 1913. Almost as if to echo the high-tech aspects of the fair in general, the art shown at the Palace of Fine Arts included a large selection of Italian Futurist work, as the Armory Show did not.

James A. Ganz, the principal curator of the show, says he intended that contrast to shake up visitors to the De Young. “They’ll experience that surprise, that same shock, that visitors did in 1915,” he says, “when having been soothed by the harmonious color scheme of the Jewel City and French Impressionism, they found themselves in a raucous roomful of paintings by Boccioni, Russolo and Severini.”

The passage of time has made the respectable art seem less worthy of automatic acceptance and made the perversity of the avant-garde seem less novel, but the sense of surprise and discomfort is still there.

What are the dates of this PPIE exhibition. Thanks

It ran from October 2015 through January 10, 2016. Here’s more information from the museum: https://deyoung.famsf.org/jewel-city