FLW tiles in Taliesin red

December 22, 2019 § Leave a comment

Frank Lloyd Wright’s signature red tile.

ARCHITECT AARON GREEN, who lived in an apartment overlooking San Francisco’s Lafayette Park for many years, helped Frank Lloyd Wright establish an office here in 1951 at 319 Grant Avenue.

Green’s mother-in-law, Jeannette Pauson Haber, lived near him at 2510 Jackson Street, on Alta Plaza Park, with her sister, Rose Pauson, who was a former client of Wright’s. In 1940 she had built the Pauson House in Arizona, which was destroyed by fire in 1943.

Rose was a painter, and Jeannette a ceramicist. When Wright decided to create red tiles, inscribed with his initials, to be affixed to a select number of his buildings, he asked Jeannette to fabricate them. Wright provided a drawing of what he wanted; Jeannette formed the tiles; Aaron Green inscribed the initials — FLLW — into each one; and Jeannette produced the “Taliesin red” glazed surface that Wright specified.

Among the Bay Area buildings that Wright designated as worthy of bearing the tiles were the V.C. Morris shop on Maiden Lane — his only building in San Francisco and a precursor to the circular Guggenheim Museum in New York — and the Marin County Civic Center, which was completed by Aaron Green after Wright’s death.

— From Frank Lloyd Wright and San Francisco, by Paul V. Turner, published by Yale University Press.

Maybeck’s Roos House changes families

February 11, 2018 § 1 Comment

IN THE dwindling days of December, an historic Presidio Heights Tudor sold for the first time — ever — making it the biggest single-family home sale of 2017 in San Francisco.

Bernard Maybeck’s Roos House, at 3500 Jackson Street, sold for $11 million, down from its original asking price of $16 million. Since its construction in 1909, the home had been passed down through family members, making this its first-ever sale.

♦

“Architecture is Life-Poetry,” Maybeck once said, quoting Louis Sullivan. The house Maybeck designed in 1909 for the Leon L. Roos family “was definitely Life-Poetry,” wrote Sally Woodbridge in her definitive book, Bernard Maybeck: Visionary Architect.

Woodbridge wrote of the Roos House:

In Mrs. Roos, Maybeck had a client whose interest in theater paralleled his own. The house was a wedding present from her father, Morris Meyerfeld, who was a partner in the Orpheum Theater Circuit company. He had taken Elizabeth Leslie with him when he traveled to Europe in search of talent, and these tours gave her a lasting enthusiasm for the theater and for theatricality. When she heard that Mr. Maybeck designed theatrical houses, she rejected the architect her father had chosen and hired Maybeck.

The skylit entrance hall of the Roos House.

At about 9,000 square feet, this is Maybeck’s largest San Francisco residence. It has two distinct sections: a two-story front part with dining room, entrance hall, kitchen and service spaces on the ground floor and bedrooms above; and a back part with only one floor but nearly the same height as the front part. The back part contains the great two-story living hall, the largest room in the house. Though difficult to ignore for other reasons, the house does not immediately reveal its considerable size. Instead of the grand entrance typical of mansions of the time, the front door is at the end of the loggia on the east side of the house, and it is not visible from the street.

The Roos family entertained frequently and formally. Their guests would approach the house through the loggia, which serves as an open foyer, and enter the low-ceilinged, skylit entry. From this point the sequence of spaces along the lengthy north-south asix is visible. The passage from the dining room at the front to the secondary living room, or alcove, at the back is also a progression from the closed and private street side to the more open garden side. The low-ceilinged alcove is a setting for contemplation of the view through the large window overlooking the Presidio grounds and Marin County across the bay.

While the guests proceeded into the living hall, the hosts would descend from the upper floor by means of a stair hidden behind a wall and appear on a stagelike landing to greet those assembled in the hall. The landing, raised four steps above floor level, forms one end of a cross axis anchored on the opposite side of the room by a caststone fireplace that rises to the ceiling. After making an initial appearance, the hosts would usually stand by the hearth and receive their guests less formally. Dr. Jane Roos, who inherited the house in the late 1970s, recalls that she first saw her mother-in-law dressed in a tea gown, standing by the fireplace.

The Rooses had a wonderful time living a baronial life. Leon Roos, who was an owner of Roos Brothers, one of San Francisco’s major men’s furnishing stores, designed a family crest and commissioned furniture from Maybeck to complement the pieces they purchased in Europe and elsewhere.

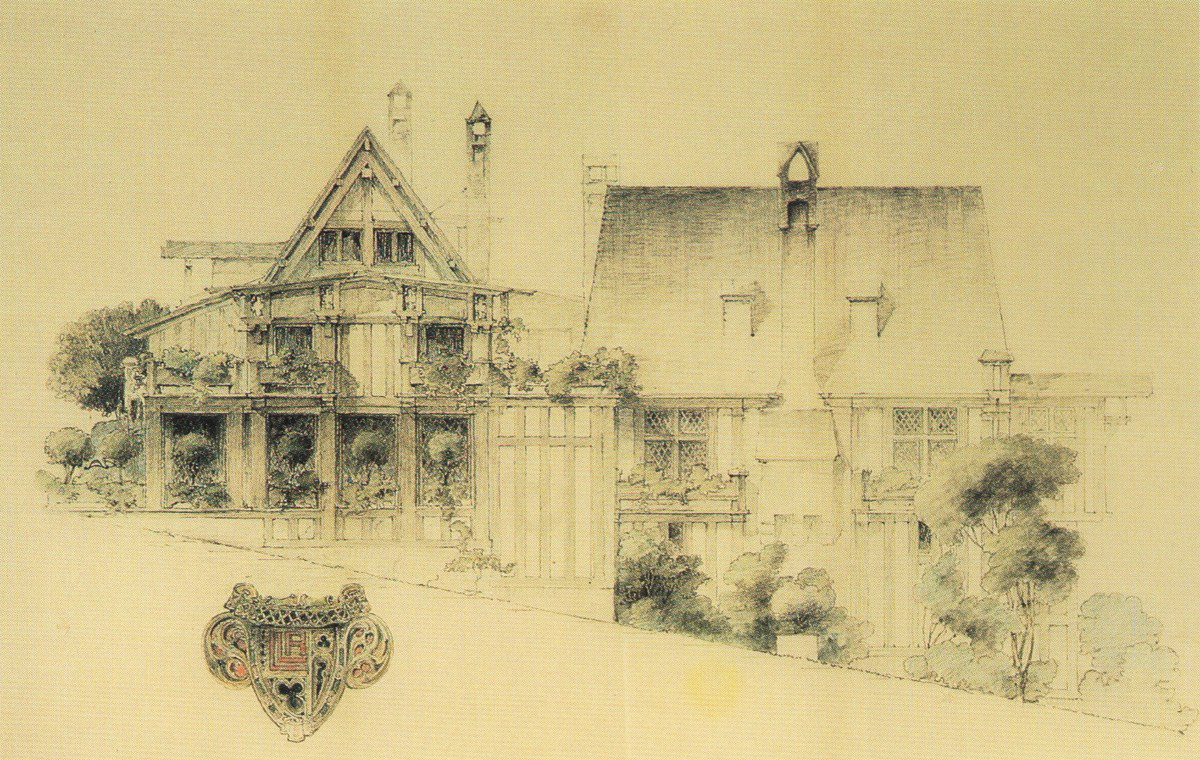

Maybeck’s presentation drawing of the Roos house, with the family crest.

Maybeck, meet Frank Lloyd Wright

December 15, 2016 § Leave a comment

Bazett House, 1939, Frank Lloyd Wright Archive

IN 1939, after seeing his Hanna House at Stanford, Sidney and Louise Bazett retained legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright to design a new house for them nearby in Hillsborough, south of San Francisco.

When construction began the next year, the Bazetts agreed to Wright’s request that one of his apprentices, Blaine Drake, come to the site during construction to supervise and make sure Wright’s intentions were being carried out — with the apprentice to be housed and fed by the Bazetts.

Even during construction, the house was already attracting attention, and another legendary architect stopped by to take a look. As the roofs were being finished, Blaine Drake reported to Wright: “Bernard Maybeck, the architect, was over to see the house — he was both puzzled and intrigued.”

— From Frank Lloyd Wright and San Francisco by Paul V. Turner

What about SFMOMA?

May 10, 2016 § Leave a comment

In the inaugural Art of Northern California exhibition, three Thiebauds and an Arneson.

SO WHAT ABOUT San Francisco’s extravagant new Museum of Modern Art? Well, it’s big, that’s for sure. And there is much to recommend:

• Photography gets respect. There are hundreds of photographs in dozens of galleries — almost the entire third floor and more. The “California and the West” exhibition is terrific.

• California art gets greater prominence, including a three-part “Art of Northern California” inaugural exhibition.

• The highlights of the permanent collection — Matisse! Rivera! — still have pride of place in the still-grand second floor galleries.

• Unlike much of the Fisher Collection, which will appeal to some more than others, the Calder sculptures are a delight, especially in front of the living wall.

Mostly the new building works. It is a huge cruise ship beached between the Mario Botta building (a relic from all the way back in 1995) and Timothy Pflueger’s magnificent Art Deco backdrop from the 1920s. But it is functional — and it has beautiful wooden stairs and windows framing views of the city.

Two complaints about the architecture:

• Botta’s beautiful entry has been eviscerated and replaced by a vast empty space with the kind of lean-to staircase that might take you over the dunes onto the beach. A crime.

• And the magisterial enfilade of galleries marching across the front of the second floor has been blocked off to create separate spaces, presumably. Surely this is not permanent.

Go and visit. There are much worse things than another new museum in town.

MORE: “Transforming SFMOMA“